BACK TO SCHOOL - with Cath Kitchen: Parenting, Partnership, and Medical Needs in the Classroom

Every September I write a ‘Letter to the Teachers’ about my daughter’s single ventricle heart. This year, I turned to expert Cath Kitchen to explore how trust, courage, and partnership help children with medical needs thrive in school.

It's been four years since I first wrote our Letter to the Teachers - and two years since I published it here on the blog. The purpose was always simple: to let the "new members" of our daughter's caretakers' team know what living with a single ventricle heart means in the day-to-day realities of school. What she can do, what she can't, what to look out for - and, equally important, what not to worry about.

The letter changes every year, because her needs and challenges change. Updating it has become a ritual. I marvel at her progress, but I also record setbacks and new risks. It's both factual and deeply personal: part medical briefing, part mother's love letter.

Teachers have often told me it helps them, not only for the practical guidance, but also to ease the fear of dealing with the unknown. None of them had ever taught a child with such a complex heart condition before our Emanuela walked into their classroom.

Still, I sometimes wonder: do they really find it useful, or are they just being polite? After years of rewriting, I've started to feel a little "novelty fatigue." Everyone knows her now, the systems are in place, and not much has changed. Is it worth writing it again?

To find perspective, I spoke to Cath Kitchen, a leading UK expert in education for children with medical needs and Chair of the National Association for Hospital Education. She has spent decades working with children whose schooling is disrupted by illness, and today she leads a network of schools dedicated to them.

Her first point hit home:

For parents, there is the fear that the school does not understand the medical condition well enough, that they won’t follow the plan, that you are not in control when they are in school and they won’t call you when they need to.

For the school, they too are fearful of ‘doing the wrong thing’. They may not have the desired number of staff to provide the support needed, or lack training in the medical condition.

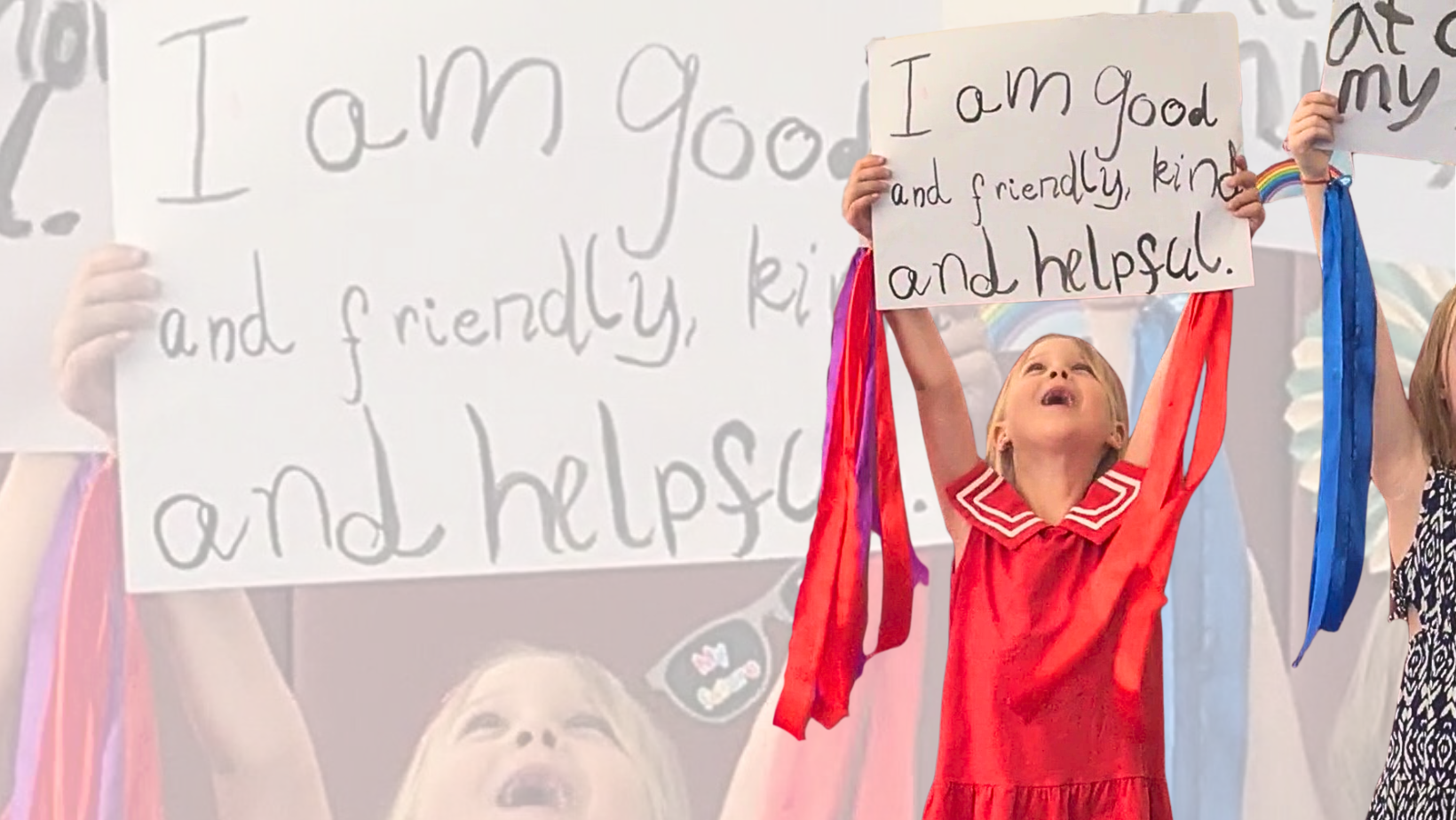

For the child, they may be anxious and also a little fearful. Will they be made to feel different?

Cath Kitchen, Chair, National Association for Hospital Education (UK)

Her words capture the triangle we live in: parent, teacher, child - each of us with our own fears.

My annual letter can't solve all of that, but it does serve as an opening gesture: my step forward in letting the school know I trust them, but also that I am here to support them. It's an invitation to cooperation.

Primary Years and What Lies Ahead

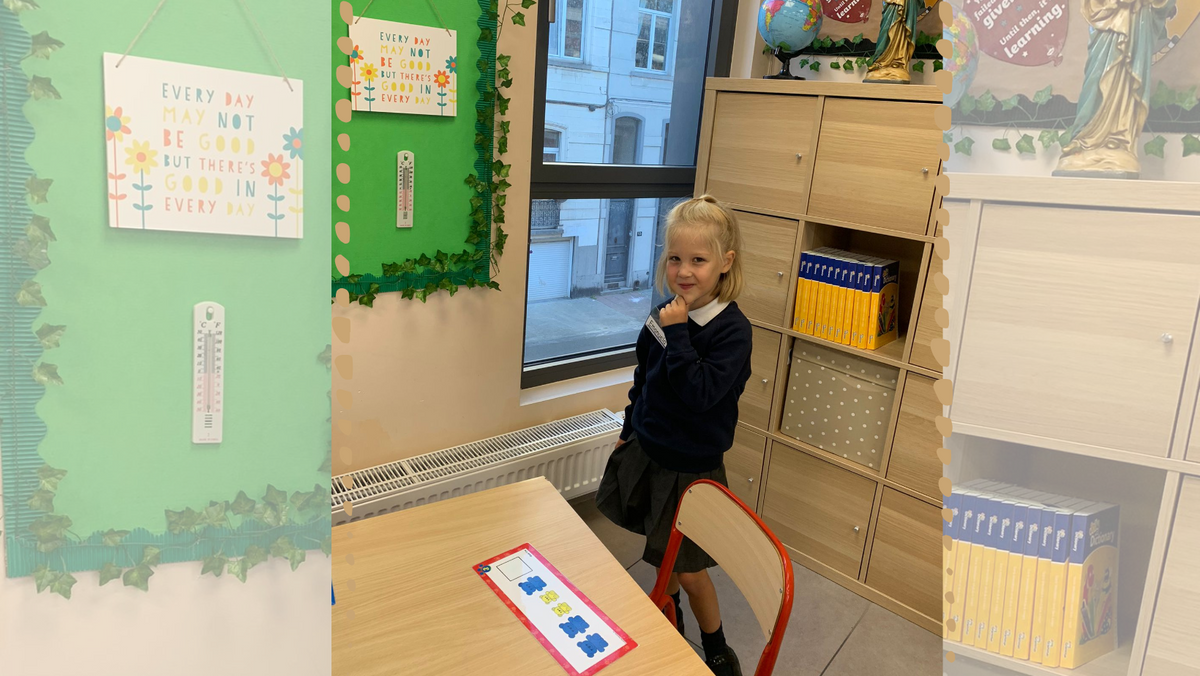

We're still in primary school, the first few years considered simpler. Routines are stable, and children more accepting of difference. I remember our Emanuela having a phase of showing her scar to her class in Year 1, at the age of five. The following year, she brought children's books about being different and having a scar, which her teacher read to the class.

As Mrs. Kitchen explained, this stage has advantages:

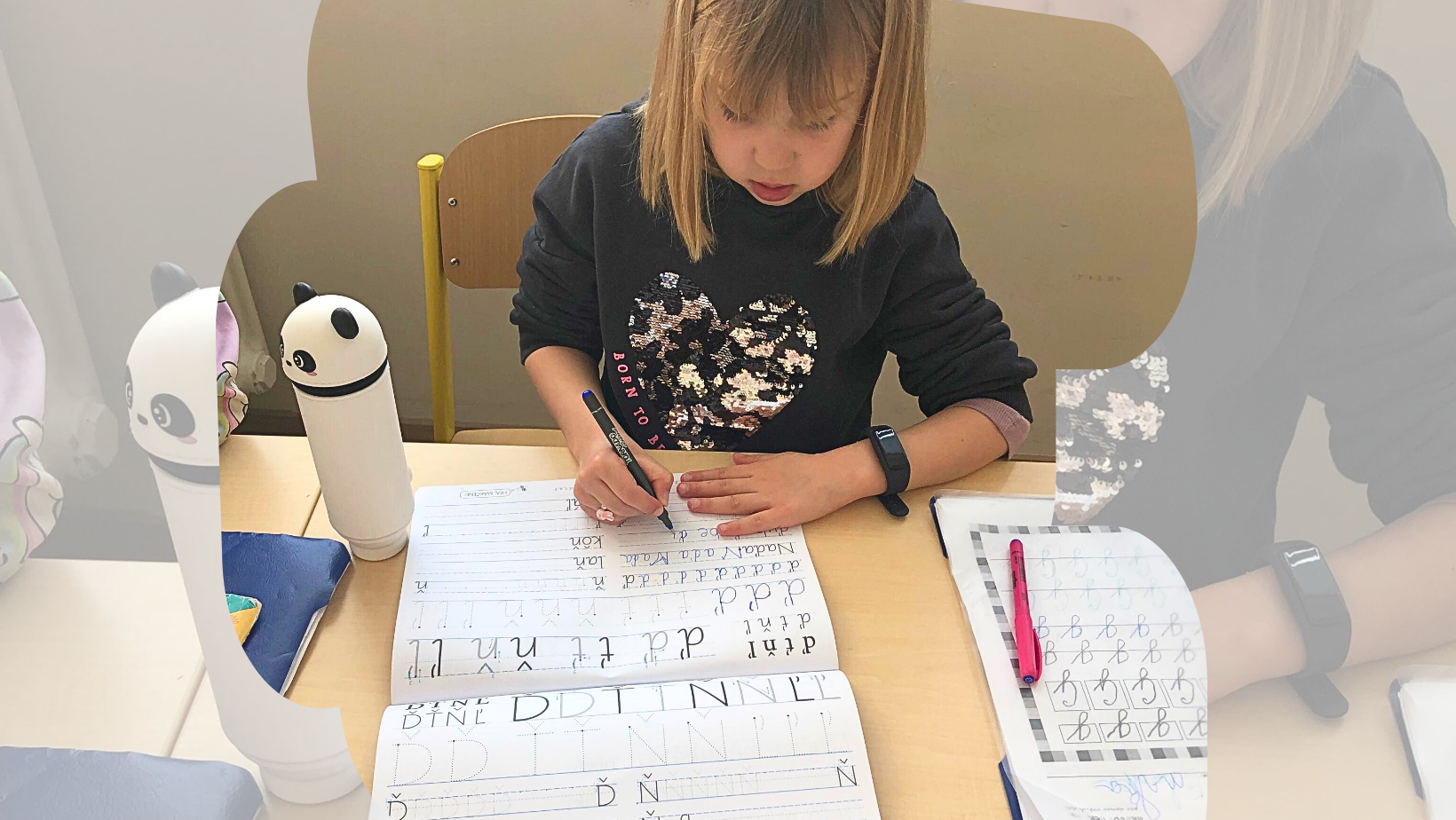

In the primary phase, other children are more accepting of differences. Most lessons are in one classroom with the same teacher, who can really get to know the child and their parents, and provide personalised support. In the secondary phase, there are more challenges. Children move around large schools, with many teachers, crowded corridors, heavier workloads, and increasing peer pressure. If a child misses school, they may feel isolated from friends.

Cath Kitchen, Chair, National Association for Hospital Education (UK)

We are not in secondary school yet, but we got a glimpse when we moved countries a few months ago, mid-school year. Emanuela had to start over: new friends, new teachers, new rules. We were lucky that her main teacher was a young woman eager to learn and willing to push the limits of a system that often prefers to stay stuck.

Within days, Emanuela found her place. The social worker and psychologist, with whom I had made a prior "secret" plan to support our daughter quietly, stepped back, and everyone kept each other in the loop.

That experience showed me what Mrs. Kitchen also stressed: teachers don't need to be medical experts, but they do need curiosity, humility, and openness to ask questions.

A teacher doesn’t need to be an expert in the child’s medical condition, but they do need to understand how a disability impacts a child's ability to learn. They should never be afraid to say what they don’t know and ask. Parents and the child are the experts. What matters is regular communication and remembering that school is not just about learning - it's about belonging.

Cath Kitchen, Chair, National Association for Hospital Education (UK)

Preparing for School Together

Before we moved, we first visited the new school with Emanuela. We have always encouraged her to ask questions and share her opinion. But we also set meetings without her to speak more openly with school staff. I firmly believe that being prepared helped all of us.

What can parents actually do before the first bell rings?

- Arrange a meeting with key staff before the transition, and include your child if possible.

- Offer to speak to the whole staff team so everyone knows what to do in an emergency.

- Set up regular check-ins with one key contact.

- Support the school in creating an Individual Healthcare Plan and risk assessments for specific subjects.

All of the above applies not only for the start of school or changing schools, but also - and perhaps most importantly - when a child is absent due to long hospitalizations, complicated procedures, or changes in their health. In those cases, keeping the social-emotional side in focus is crucial.

It is really hard to think about your child’s social and emotional development when they are unwell, but this is absolutely critical to their wellbeing. If they can't go out in the playground, ask the school to make sure there are friends allocated to stay in and play with them. If they miss school, work with the school to set up channels of communication so they can keep in touch with peers online, by phone, or with technology like the AV1 robot. Social contact supports recovery and eases the transition back to school.

Cath Kitchen, Chair, National Association for Hospital Education (UK)

The Letter and it's Fifth Edition

So, will I write the letter again this year? Yes. Even if much of it stays the same, it marks the start of a conversation. It tells teachers we're in this together. It reassures Emanuela that we've prepared her world so she can walk in freely. And it reminds me that while I can't control everything, I can build bridges.

Back-to-school will always be a little harder for children with complex medical needs. But with openness, curiosity, and cooperation, it can also be a time of hope - another chance for our children not just to learn, but to find their place under the sun.

Cath Kitchen has just edited Including Learners with Medical Needs in School — a practical guide for teachers and schools on how to support children with complex health conditions. Packed with strategies, case studies, and ready-to-use templates, it’s essential reading for anyone working with pupils with medical needs.